Being a kid in America is safer than it’s ever been.

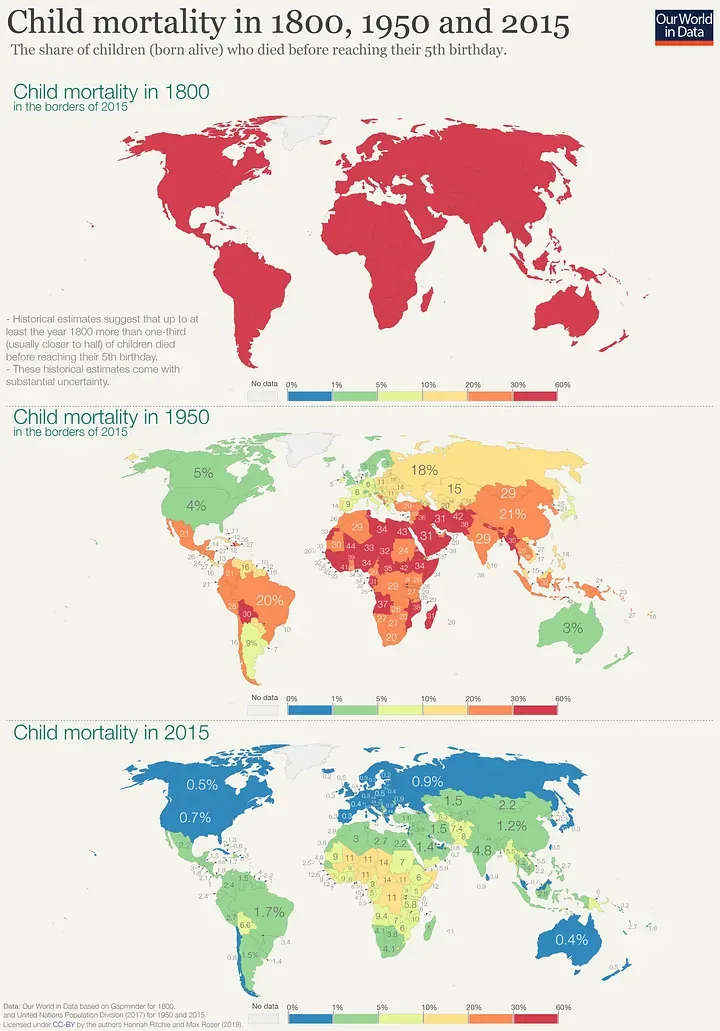

Medical advances — especially vaccines against childhood diseases — have created a world in which kids don’t die nearly as much as they used to. Two hundred years ago, child mortality was around 50% (meaning that half of children died before age 5!) everywhere in the world.

Even in the 1950s, 4% of American kids died before their fifth birthday. Now, that number is 0.7% — it could get better, I’m sure, but it’s a miracle compared to what humanity has seen in the past.

Kids engage in less risky behavior than they used to — teen pregnancy has declined 75% since the 1990s, teens get into fewer fights than they used to, and alcohol and drug usage has plummeted.

Kids wear bike helmets now, they get strapped into car seats, their play is supervised, they’re tracked via GPS, and they’re much more likely to be enrolled in after-school programs, sports, or daycare than to be sent out into the neighborhood to roam until dinnertime.

“Helicopter” and even “snowplow” parenting — in which parents are extremely involved in their kids’ lives, making sure they have their needs and wants promptly met — are dominant American models of raising kids, especially in upper-middle-class communities.

You could make a strong argument that it’s never been safer to be a kid in America.

So why are kids so anxious?

In a 2019 study — conducted before the global pandemic took a serious toll on many young Americans’ mental health — close to a quarter of American undergraduates said that they had been diagnosed with an anxiety disorder, more than twice as many as a decade before. Lots of mental health diagnoses — depression, ADHD, bipolar disorder — have soared in recent years, but none as sharply as anxiety.

Anxiety is a condition characterized by runaway fear and worry, in which the mind perseverates on potential problems to the detriment of a person’s quality of life.

So why, in a world where we have managed to remove many of the most serious threats from kids’ lives, are so many American kids beset by a persistent and unshakeable sense of fear?

There are a lot of possible culprits.

First, there’s American safety culture. We’re a country awash in litigation. In order to avoid lawsuits, companies warn us about each and every threat, no matter how minuscule the threat really is.

So every prescription drug commercial is a litany of possible side effects. Every time a kid goes to a birthday party at an indoor trampoline park, her parents have to sign a waiver acknowledging that she could suffer horrific injuries there. There are warnings on all sorts of consumer products about potentially “harmful chemicals” — even those that don’t really contain said chemicals — because it’s easier for companies to label everything and avoid potential legal action.

American kids grow up amidst constant messaging that everyday life, the environments they live in, and the products that they use are dangerous when they’re really not that dangerous.

A lot of aspects of our safety culture make us feel less safe, but they only make us marginally more safe.

Think about active-shooter drills. Many schools in America now ask their students to simulate various horrifying scenarios — a sniper out on the basketball court, or an intruder in the science wing. Though America has way too many, school shootings are still exceedingly rare.

According to Harvard risk scholar David Ropeik, the risk of dying in a school shooting is “far lower than almost any other mortality risk a kid faces, including traveling to and from school, catching a potentially deadly disease while in school, or suffering a life-threatening injury playing interscholastic sports.”

Are we helping kids by making them simulate horrific school shootings every year? I’m not sure. In the event of an actual shooting, I doubt the training will be terribly useful to kids (they feel kind of like the old duck-and-cover drills from the Cold War). But school-shooting drills send kids a message: Be afraid. Get ready to hide under your desk or break a window or throw your math book at a gunman. It could happen to you.

Then there’s the news and social media. The news media has a couple of important leanings — they focus on bad news more than good news, and they want to make us believe that whatever is going on in the news each day really matters.

This was not so bad when the news was on for half an hour a day, half-watched while families ate dinner. But now, you can doomscroll through bad news all day, every day. The experience of swimming in the news all the time warps our understanding of the world because it seems like the terrible things on the news are everywhere when the very reason the media is reporting on them is that they’re unusual.

This isn’t to say that there aren’t bad things happening in the world — there are! But I think the news often misleads us about how bad things are, making it hard for us to identify which dangers are real and important and which aren’t.

It’s why my dad, who consumes mostly Fox News and local news, thinks that he’s taking his life in his hands every time he goes downtown in our relatively safe city to see a baseball game. It’s why the foreign exchange students who came to our school last year thought that they were in imminent danger of dying in a school shooting. And it’s why relatively plugged-in American kids think everything is terrible and the world is ending.

But most kids aren’t reading the New York Times. They’re ingesting the news indirectly, through social media.

The experience of scrolling through the news on a smartphone is, by nature, anxiety-inducing.

You’re trapped by the algorithm while terrible events flit past your consciousness, one after another. Most of what you read is hyperbole, designed to stoke strong emotions, in order to keep you engaged. You don’t have time to really process any of what you’re seeing, assess its validity, or gauge its importance. This is bad enough for adults — now try doing it with a teenage brain.

And finally, there’s the possibility that we’re protecting our kids too much. We all want our kids to be, and feel, safe. It’s a primal drive for every parent. But modern American parenting may have gone too far in this direction. A lot of kids are supervised all the time lest something truly horrific happens to them, even though abductions and the like are vanishingly rare.

We keep kids safe even from the little things. In school, many students are shielded from any potential failure. The problem is that, if kids never experience failure in low-stakes situations like a math quiz, they will not know what to do when they face real problems. We may have tried a bit too hard to keep our kids from experiencing frustration or sadness.

Living a childhood without enough rough edges, without a little risk and a little failure, may have made it difficult for a lot of kids to handle even small setbacks. It seems like a lot of young Americans have come to believe that they’re fragile, that there’s danger everywhere, and that life is too hard to handle.

Some experts believe that American helicopter parenting has gone too far. They think that parents and schools should give kids more independence and allow them to learn to navigate a reasonable amount of risk. If you buy this theory, the good news is that the solution is free and easy — just send your kids out to play! Give them a little independence!

Americans should congratulate ourselves — we have done a remarkable job of protecting our kids from actual danger. It’s never been safer to be a kid in America. But we haven’t protected kids from feeling like there’s danger all around.

So how do we raise kids with a reasonable attitude toward risk? How do we make sure that the next generation of young people isn’t burdened with constant fear, even though they’re really quite safe?

You can read George's writing on history here and his essays about politics, culture, and the environment here.

Member discussion